It was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow who said, “Lives of great men all remind us, we can make our lives sublime, and, departing, leave behind us, footprints on the sands of time.” And Alex Haley, the author of “Roots,” stated:

In all of us there is a hunger, marrow deep, to know our heritage – to know who we are and where we came from. Without this enriching knowledge, there is a hollow yearning. No matter what our attainments in life, there is still a vacuum, an emptiness, and the most disquieting loneliness.

There are things in all of our histories that we may wish we could change, but alas we are powerless to turn back the hands of time and make those changes ourselves. What we can do, however, is learn from our past. We can learn from the examples of our forefathers, who though life may not have been the best for them at times, traversed many trails of tears and still pressed forward with every ounce of strength and courage that they could muster to blaze trails of hope, and to build bridges to a brighter tomorrow for those who would come after them.

Emancipation of Slaves and the Freedmen’s Bureau

The Emancipation Proclamation was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by President Abraham Lincoln on 1 January 1863. It changed the legal status, as recognized by the United States federal government, of 3 million slaves in the designated areas of the South from “slave” to “free.” It was issued as a war measure during the American Civil War, directed to all of the areas in rebellion and all segments of the executive branch, including the Army and Navy, of the United States. It also proclaimed the freedom of slaves in the ten states that were still in rebellion, and thus applied to more than 3 million of the 4 million slaves in the U.S. at the time. The abolition of slavery in Texas, however, did not occur until two years later, on 19 June 1865, when a Union General in Galveston, Texas, read aloud the contents of “General Order No. 3,” which proclaimed the total emancipation of slaves.

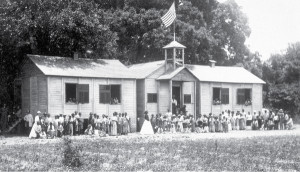

The Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, which established the Freedmen’s Bureau on 3 March 1865, was initiated by President Abraham Lincoln and was intended to last for one year after the end of the Civil War. It was established to aid “freedmen” (freed slaves) in 15 states and the District of Columbia during the Reconstruction era of the United States. The Bureau was made a part of the United States Department of War and was given the authority to help African Americans find family members from whom they had become separated during the war. It also arranged to teach them to read and write, which was considered critical by the freedmen themselves, as well as the government, by opening schools. Bureau agents also served as legal advocates for African Americans in both local and national courts, mostly in cases dealing with family issues. The Bureau also managed hospitals, and encouraged former major planters to rebuild their plantations and urged freed Blacks to gain employment. All the while, the Bureau kept a watchful eye on contracts between the newly free labor and planters, and encouraged both Whites and Blacks to work together as employers and employees, instead of masters and slaves.

The Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, which established the Freedmen’s Bureau on 3 March 1865, was initiated by President Abraham Lincoln and was intended to last for one year after the end of the Civil War. It was established to aid “freedmen” (freed slaves) in 15 states and the District of Columbia during the Reconstruction era of the United States. The Bureau was made a part of the United States Department of War and was given the authority to help African Americans find family members from whom they had become separated during the war. It also arranged to teach them to read and write, which was considered critical by the freedmen themselves, as well as the government, by opening schools. Bureau agents also served as legal advocates for African Americans in both local and national courts, mostly in cases dealing with family issues. The Bureau also managed hospitals, and encouraged former major planters to rebuild their plantations and urged freed Blacks to gain employment. All the while, the Bureau kept a watchful eye on contracts between the newly free labor and planters, and encouraged both Whites and Blacks to work together as employers and employees, instead of masters and slaves.

Freedmen’s Bureau Project Announced

On Friday, 19 June 2015 (“Juneteenth”), the 150th celebration of Emancipation Day, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, FamilySearch International, a nonprofit organization sponsored by the Church, and African-American history organizations, announced the joint Freedmen’s Bureau Project which will release 1.5 million digitized hand-written records that contain the names of up to 4 million former slaves collected by agents of the Freedman’s Bureau at the end of the Civil War.

The project, which is a partnership between Family Search, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Afro-American Historical & Genealogical Society, and the California African American Museum, was announced at a press conference held in the California African American Museum in Los Angeles, California. It will make the records available for free online at a new website, discoverfreedmen.org. The press conference, hosted by Jermaine and Kembe Sullivan, who were featured in the 2014 movie “Meet the Mormons,” was streamed live online and included simultaneous gatherings at 31 other locations, including the Underground Railroad Museum and the National Civil War Museum.

Release of Records Reveal Critical Links to the Past

According to Deseret News, Elder D. Todd Christofferson of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ stated during his remarks that the Freedmen’s Bureau records have the potential to help “reunite the black family that was once torn apart by slavery.” Rev. Cecil L. Murray of the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at the University of Southern California in his remarks emphasized that “freedmen” (freed slaves) “would not have had any place to stay, any place to sleep, or any food to eat had it not been for the concept of the Freedmen’s Bureau.”

The Freedmen’s Bureau records contain information about former slaves such as marriages, military pensions, and labor contracts and trials that would have otherwise been lost forever. Paul Nauta, spokesman for FamilySearch, commented:

African-Americans who tried to research their family history before 1870 hit a brick wall because before 1870 their ancestors who were slaves and showed up as ticks or hash marks on paper. They didn’t have a name. The slave master would just have tick marks.

With the availability of these valuable records, people like Houston minister Monique Lampkin who has long yearned to know more about her roots will be able to learn the names of those ancestors who were emancipated slaves in 1865 and their contributions.

With the availability of these valuable records, people like Houston minister Monique Lampkin who has long yearned to know more about her roots will be able to learn the names of those ancestors who were emancipated slaves in 1865 and their contributions.

Using the Freedmen’s Bureau records in conjunction with the Freedmen’s Bank records, minister Lampkin and her mother were able to discover vital information which they consider “sacred and priceless” in a child support document, a request for wages due, a character reference and in additional information about family residences. And now, with these records being made available online, African-Americans will have a vast library of information from which to draw, thus providing a vital link to their past which will enable them to learn more about their family and where they came from.

Hollis Gentry from the Smithsonian commented that the records will do more than just connect Black families of the present with their family members of the past:

I predict we’ll see millions of living people find living relatives they never knew existed. That will be a tremendous blessing and a wonderful, healing experience. These records were created when these people were alive and immediately after they were freed. You get a sense of them, of their hopes and dreams.

Keith L. Brown is a convert to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, having been born and raised Baptist. He was studying to be a Baptist minister at the time of his conversion to the LDS faith. He was baptized on 10 March 1998 in Reykjavik, Iceland while serving on active duty in the United States Navy in Keflavic, Iceland. He currently serves as the First Assistant to the High Priest Group for the Annapolis, Maryland Ward. He is a 30-year honorably retired United States Navy Veteran.